STS-59, Endeavour, Space Radar Lab 1 — April 9-20, 1994 April 9, 2013

Posted by skywalking1 in History, Space.trackback

Twenty years ago, our STS-59 crew completed the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test in preparation for our April 9 launch. At pad 39A, with Endeavour, are Rich Clifford, Kevin Chilton, Sid Gutierrez, Linda Godwin, Tom Jones (the sole rookie), and Jay Apt. Boy, was I excited: just over two weeks til launch! (NASA KSC-94PC-468)

Tom Jones with Endeavour’s SRB and ET stack on Launch Pad 39A. The orbiter is enclosed by the gray protective structure. (NASA ksc-394c-1160.22)

Our STS-59 crew during our countdown rehearsal on 3/23/94. Here we gather outside Endeavour’s hatch in the Pad 39A White Room. Left to right are Rich Clifford, Jay Apt, Linda Godwin, Tom Jones, Kevin Chilton, and Sid Gutierrez. (NASA KSC-394C-1160.09)

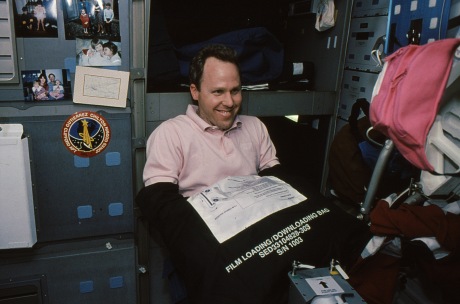

On Endeavour’s middeck, Linda Godwin (right) and I wait out the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test (TCDT) on 3/24/94. I caught a brief nap during the 3-hour mock countdown. (NASA photo by Andy Thomas).

I’ve written about the Space Radar Lab 1 mission, STS-59, in my book, “Sky Walking: An Astronaut’s Memoir.” But here I’ll add some details not included in the book, and some of the many hundreds of photos our crew returned to preserve our memories of these superb 11 days in space. I’ll add thoughts and photos during the coming eleven days, with the idea that the post can become an archive for the STS-59 crew and team.

As soon as we entered quarantine in late March in Houston, shuttle managers postponed the April 7 launch a day for engine turbopump inspections. Then our first launch attempt on April 8 was postponed because of high winds at Kennedy Space Center, violating the runway crosswind limits for the orbiter in case of an emergency return to the Cape. Our crew sat strapped in on the pad for about five hours as we waited for the winds to abate, but they never did. The parachute pack and its emergency oxygen bottles become extremely annoying after five hours strapped in the seat. The scrub under clear blue skies was a disappointment, but we were coming back the next day.

This was my first space shuttle launch, and it lived up to my expectations in every day. Jolts, rumbles, screaming slipstream penetrating the cabin walls, 2.5 g’s during first stage–I could barely register all the physical and emotional sensations during the 8.5 minutes of ascent. I was gratified to have Linda Godwin seated to my left on the middeck — a veteran and friend I could turn to for reassurance during this vibration-filled ride to orbit. We were smiling the whole time, but behind the smile is a lot of prayer. After a full minute at 3 g’s, with the Mach meter at 25, I thanked God when we arrived in orbit–Main Engine Cut-Off–and weightlessness.

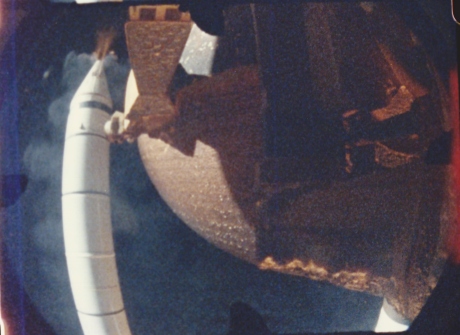

The 16mm movie camera in Endeavour’s left ET umbilical well caught the left-side SRB separating at about 2 minutes into our ascent, ~ Mach 4. You can see the forward booster separation motors still firing. (NASA STS059-16ET-1577)

Sid, Jay, Rich, Kevin, Linda, and I were about to experience an incredibly rewarding Mission to Planet Earth.

Just out of my suit on the middeck of Endeavour, helping other crewmembers get unsuited and into “orbit” clothes. 4/9/94 (NASA)

The Space Radar Lab 1 payload in Endeavour’s cargo bay. Three cutting-edge radar instruments, a CO pollution monitor, and a terrific view of the Aurora Australis. (NASA)

Our job on SRL-1, STS-59, was to act as the space component of the Space Radar Lab science team, deployed all over the world. We commanded the orbiter to point at our 400+ science targets, monitored the maneuver execution “flown” by Endeavour’s computers after our data entries, changed high rate recorder data tapes, and took voluminous science photography to provide “ground truth” about environmental conditions that might affect the radar return from the science targets. Our crew split into two shifts, Red and Blue, to run SRL around the clock. Linda Godwin led the activation on flight day 1. The Blue Shift woke up about 10 hours into the flight and took over for our first full science shift — Jay, Rich, and me. Linda, Sid, and Kevin went promptly to bed after a very long day. We soon settled into our 12-hour shift routines and explored the world for another ten days.

Rich Clifford inserts a data storage cassette into one of our 3 high rate recorders. Each tape cassette held 50 Gb of data. We carried more than 100 onboard, with a tape change about every 30 mins for 11 days. (NASA STS059-09-12)

STS-59 crew: (L to R) Linda Godwin, Kevin Chilton, Tom Jones, Jay Apt, Sid Gutierrez, Rich Clifford. (NASA)

Our crew had 14 different cameras aboard to document our science targets. A big Linhof shot a 4×5-inch negative, using box magazines which we reloaded in a light-tight bag every night. We had four Hasselblads with 70mm film, each armed with a different lens for science photography (40mm, 100mm, 250mm, and an infrared filter atop a 250mm lens). We used Nikons for in-cabin photography using 35mm film. And we used payload bay video cameras to record the swath being seen by the radar with each data take. Here’s a shot of one of our “Decade Volcano” targets, the Philippines’ Mt. Pinatubo.

Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines, which erupted in 1991, sends ash flows surging downslope under seasonal rains. Note the emerald green crater lake at the summit. (NASA STS059-L14-170)

Kevin Chilton and Linda Godwin shoot science targets on the Red Shift aboard Endeavour. (NASA sts059-13-030)

Frozen, volcanic Onekotan Island, Russia, in the Kuriles south of Kamchatka. April 14, 1994. (NASA STS059-219-065)

Each work shift on the aft flight deck was run on the clock: a constant stream of orbiter maneuvers, recorder tape changes, and intense video and still photo sessions focused on the science targets below (or above, from our point of view on the flight deck). We took turns entering the maneuvers on the flight plan into Endeavour’s computers, changing and managing the 50 Gb tape cassettes, and spotting and documenting science targets with our cameras. After each target we typed entries into a laptop documenting the weather, dust, and precipitation conditions over the science site. Night passes were a bit calmer, because the photography requirements went away for the most part. We also called down fires and other environmental phenomena of interest to the Measurement of Air Pollution from Satellites team. In between, we grabbed snacks and established comm with HAM radio operators around the globe. One generous HAM arranged to patch me through on a phone call to Liz, back in Houston. We spoke clearly across the miles; me over Hawaii, Liz with the kids back in Houston, until Endeavour carried me over the horizon. Priceless.

Linda Godwin, Kevin Chilton (left) and Sid Gutierrez have breakfast and read flight plan changes on Endeavour’s middeck. Work shifts were 12 hours, with 8 hours for sleep. The balance was spent on exercise, meals, and housekeeping. (NASA STS059-05-07)

One of Jay Apt’s best photos of the Aurora Australis from STS-59. The radar antennae are to the left, the Canadarm I robot arm on the right. (NASA)

One of my favorite lunch items — irradiated grilled chicken breast, mustard, 2 warm tortillas = chicken flying saucer sandwich (TM). (NASA STS059-19-020)

From Endeavour’s commander, USAF Col. (ret.) Sid Gutierrez:

Great! My best memories are of the crew and the Southern Aurora. It was a great group of folks to work with both on the ground and in Space. I remember the comment Linda made during an interview that generated that strange response from the ground. I would like to forget about the air in the water and everything that went with that. Chili falling asleep on the middeck while sending Emails late at night. Jay maneuvering the vehicle under Chili’s watchful eye. Rich and I waiting for anyone to get sick so we could actually give a real shot. I remember your enthusiasm at seeing all of it the first time and your incessant comments into the tape recorder so you could piece all this together later. And I remember the incredible feeling as we blacked out the lights and floated through the Sothern Aurora – like passing thorough something that was alive. But most of all I remember being able to eat a juicy hamburger with tomato and lettuce after we landed and then heading home to wives, husband and all the kids. Great memories! (April 12, 2013)

Endeavour commander Sid Gutierrez on the flight deck during with one of our Hasselblads. Earth is the unbeatable backdrop. (NASA sts059-19-004)

The varied science targets across the globe required all of us to learn many aspects of Earth system science: geology, volcanology, forestry, ecology, hydrology, oceanography, agriculture, pollution monitoring, desertification, and radar remote sensing theory, among others. One of my favorite “others” was archaeology, where our team used the SIR-C and X-SAR radars to probe dry sands and soils and reveal traces of ancient cultures beneath. The experiment mapped extensive “radar river” drainages beneath the Saharan sands, traced the Silk Road along the margin of the Takla Makhan desert, and zeroed in on caravan routes to the lost trading city of Ubar on the Arabian peninsula. Aboard Endeavour we carried a 200,000-year-old hand axe, recovered by USGS colleague Jerry Schaber in the 1980s from the banks of one of the Egyptian radar rivers. There aboard the most sophisticated technological tool of the late 20th century, we contemplated a floating example of the “high tech” used by Homo Erectus back when the Sahara was a grassy savannah, teeming with game. What technology will we possess in another 200 millennia? Will the space shuttle even be remembered? I, for one, can never forget it!

South coast of the Alaska Peninsula, with the C-shaped island enclosing Sosbee Bay, in sunglint. (NASA STS059-214-001)

Just out of frame on the left of this Alaska coastline is Veniaminoff volcano, one of the many active peaks on the peninsula. Here we see ocean currents and eddies made visible by the reflected sunlight, corroboration of ocean surface features observed by the radar lab. What a visual treat as well.

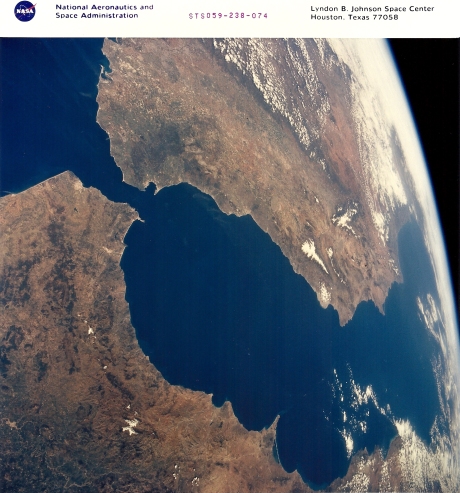

Our view from 120 miles up as we soar over Gibraltar, Spain, and Morocco. Snow caps the Atlas and Sierra Nevada ranges in Africa and Europe. (NASA sts059-238-074)

An early human hurled this axe at his prey along the banks of a stream in southern Egypt, perhaps 200,000 years ago. The USGS lent us this tool as we used our Radar Lab to map possible habitats of these ancient people, now hidden by the sands of the arid Sahara. (NASA sts-059-42-18)

The Blue Shift — Jay, Rich, and Tom — enjoys a meal after a shift on the flight deck. We generally had about 2.5 hours after finishing work to eat, clean up, and take care of middeck chores before hitting the sleep stations. (NASA sts059-14-06)

Our early spring view of the Alaskan coastal ranges, fronting the Inside Passage, was glorious. Our radar imaged glaciers around the world, like these near Mt. St. Elias, to help estimate their velocity downhill. STS059-228-94

Jay Apt shoots one of our science targets through Endeavour’s overhead windows. Mounted in the adjacent window was a large-format Linhof camera, taking a strip of overlapping photos to map each target. (NASA sts059-46-025)

An example of our crew science photography is shown below. This frame came from our 250mm lens on the large-format Linhof camera, mounted in the starboard overhead window of Endeavour’s flight deck. Sometimes we used the other Linhof body and shot handheld frames, just sighting over the lens barrel at the ground below. The Linhof magazines contained about 100 shots, and we had to reload them from film canisters while “off shift” on the middeck.

Vertical view of Strait of Gibraltar. Spain to lower left. Morocco to upper right. Note current flow in strait and along coast. The advantages of Gibraltar’s harbor are plain to see. (STS059-L19-837)

These bunks were on the starboard side of Endeavour’s middeck, stacked 4-high. Since each shift, Red and Blue, was off duty for 12 hours, we hot-bunked in the top three and used the bottom bunk for storage. Each station contained a reading light, fresh air vent, sliding privacy door, and a fleece sleeping bag. As this was my first flight, I didn’t realize that there were two bags in each bunk, clipped one atop the other, so I think I just hot-bunked in the same bag as Chili, probably. I slept in long pants, a T-shirt, and sweater, as it was a bit cool in the bunk. I even stuffed a sock in the vent to cut down on the cold breeze at “night.” I drifted off to sleep most nights with a Walkman playing a cassette for a few minutes; more than once I woke up to find the player drifting above my face, still delivering some soft music. In the morning, it would be tough to find the door in the pitch-dark compartment: turning over in the bag in free-fall meant that I had no way to determine which way was down, up, or the side that held the door. Groping around to find the reading light would usually set me straight. I had these bunks on three of my missions–they were quite comfortable, quiet, and private for sleep.

The SRL-1 Red Shift of Sid Gutierrez, Linda Godwin, and Kevin Chilton (bottom) prepares for their cozy night in Endeavour’s sleep stations. (NASA STS059-22-004)

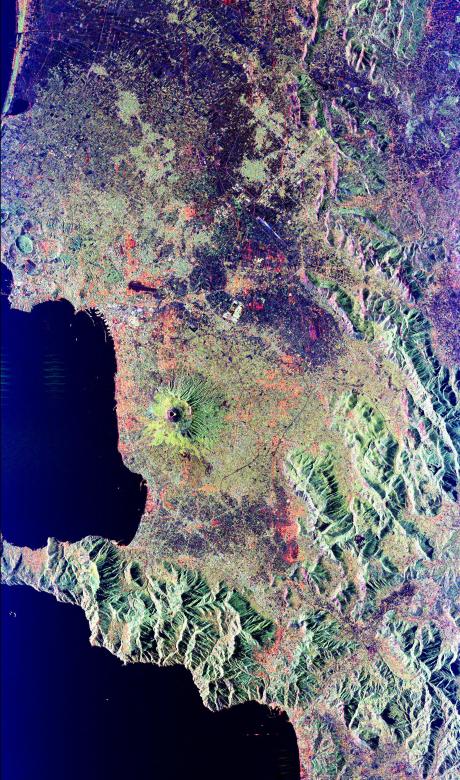

May 2013: I just returned from a trip to the Mediterranean, and viewed Mt. Vesuvius from the Bay of Naples and the lovely town of Sorrento, Italy. Here is the incredible view of this active volcano from our SRL-1 imager. Vesuvius last erupted in 1944, nearly 70 years ago. It is long overdue for another outburst. Three million people live in the Naples area. Evacuation will be a huge challenge. May the mountain sleep for a long time.

Mt. Vesuvius, one of the best known volcanoes in the world primarily for the eruption that buried the Roman city of Pompeii, is shown in the center of this radar image. The central cone of Vesuvius is the dark purple feature in the center of the volcano. This cone is surrounded on the northern and eastern sides by the old crater rim, called Mt. Somma. Recent lava flows are the pale yellow areas on the southern and western sides of the cone. Vesuvius is part of a large volcanic zone which includes the Phalagrean Fields, the cluster of craters seen along the left side of the image. The Bay of Naples, on the left side of the image, is separated from the Gulf of Salerno, in the lower left, by the Sorrento Peninsula. Dense urban settlement can be seen around the volcano. The city of Naples is above and to the left of Vesuvius; the seaport of the city can be seen in the top of the bay. Pompeii is located just below the volcano on this image. The rapid eruption in 79 A.D. buried the victims and buildings of Pompeii under several meters of debris and killed more than 2,000 people. Due to the violent eruptive style and proximity to populated areas, Vesuvius has been named by the international scientific community as one of fifteen Decade Volcanoes which are being intensively studied during the 1990s. The image is centered at 40.83 degrees North latitude, 14.53 degrees East longitude. It shows an area 100 kilometers by 55 kilometers (62 miles by 34 miles.) This image was acquired on April 15, 1994 by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR- C/X-SAR) aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour. SIR-C/X-SAR, a joint mission of the German, Italian and the United States space agencies, is part of NASA’s Mission to Planet Earth.

P-45742 July 13, 1995

SRL-1 added to our knowledge of the Earth’s impact history, by examining scars left by collisions with asteroids and comets. Here is the Aorounga impact cratter in northern Chad. Although the main crater (shown here) is visible to astronauts from orbit, our radar scans revealed (beneath the sands) two additional candidate craters. Aorounga may be a crater chain, caused by the impact of a string of comet fragments, or an asteroid accompanied by a couple of moonlets. I spent hours searching the landscape below for the circular forms of impact craters; it’s a pattern the human eye easily locks onto from orbit.

The impact of an asteroid or comet several hundred million years ago left scars in the landscape that are still visible in this spaceborne radar image of an area in the Sahara Desert of northern Chad. The concentric ring structure is the Aorounga impact crater, with a diameter of about 17 kilometers (10.5 miles). The original crater was buried by sediments, which were then partially eroded to reveal the current ring-like appearance. The dark streaks are deposits of windblown sand that migrate along valleys cut by thousands of years of wind erosion. The dark band in the upper right of the image is a portion of a proposed second crater. Scientists are using radar images to investigate the possibility that Aorounga is one of a string of impact craters formed by multiple impacts. Radar imaging is a valuable tool for the study of desert regions because the radar waves can penetrate thin layers of dry sand to reveal details of geologic structure that are invisible to other sensors. The image was acquired by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/X-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR) on April 18 and 19, 1994, onboard the space shuttle Endeavour. The area shown is 22 kilometers by 28 kilometers (14 miles by 17 miles) and is centered at 19.1 degrees north latitude, 19.3 degrees east longitude. North is toward the upper right. The colors are assigned to different radar frequencies and polarizations as follows: red is L-band, horizontally transmitted and received; green is C-band, horizontally transmitted and received; and blue is C-band, horizontally transmitted, vertically received. SIR-C/X-SAR, a joint mission of the German, Italian and United States space agencies, is part of NASA’s Mission to Planet Earth program. P-46712 March 20, 1996

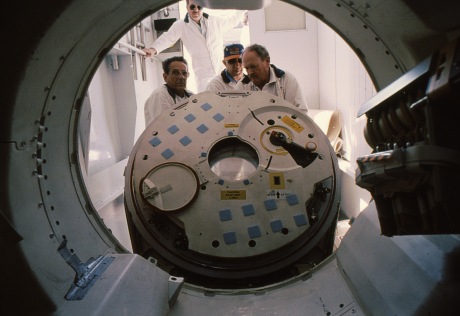

Flight Day 9 called for a thorough pre-landing check of our reentry systems. The pilots, with Rich, our flight engineer and MS-2, stepped through hydraulic systems, flight computers, auxiliary power units (APSs), and thrusters to verify proper operation. We observed systematic thruster firings from the flight deck, and watched our elevons on the wing trailing edges rise and fall, driven by the now-awakened APU’s and hydraulic systems. Endeavour was coming fully alive; all was in readiness for entry the next day.

On Flight Day 9, Sid, Chili, and Rich ran through our flight control system checkout on Endeavour’s flight deck.

NASA STS059-12-035.

Landing for our STS-59 crew came too soon, after 11 days in orbit. We had planned a 9-day mission, but our flight control team anticipated that power conservation aboard Endeavour would extend our mission to ten full days. Good power management by our payload team and Mission Control (and our keeping the lights and electricity consumption to a minimum in the cabin) secured that extra day. Our reentry was planned for April 19, but Kennedy Space Center weather prevented a return to the Florida landing site. We waved off the landing and returned to limited Earth observations for a final day; my Blue Shift went to bed immediately for 6-8 hours, then took over from our Red Shift for final cabin stowage and payload deactivation.

On April 20, weather at Kennedy was still NO-GO, so we targeted Edwards AFB in California for landing. Our crew was disappointed to not be heading for our families in Florida, but satisfied to be heading back to Earth with our successful science mission completed. Reentry over the nighttime Pacific was a spectacular experience–the plasma pulsing around our cockpit windows provided a mesmerizing light show that I’ll never see equaled. I was perched upstairs in the MS-1 seat next to Rich Clifford, MS-2. We aided the pilots, Sid and Kevin, as they guided Endeavour into southern California and our line-up for landing at Edwards.

Ripping over the California coast at more than Mach 5, it seemed to me that we’d never slow down enough to make the Edwards runway–I agreed with Sid’s assessment that “we’re headed for a landing in Arkansas!” But our flight computers were right on the money. Sid took control and put us gently on the concrete of Runway 22, an exhilarating touchdown for all of us aboard. Read about the entire return to Earth in “Sky Walking: An Astronaut’s Memoir.” Great landing, Sid and Kevin! Thanks a million for bringing us all home.

The main landing gear of the Space Shuttle Endeavour touches down at Edwards Air Force Base to complete the 11 day STS-59/SRL-1 mission. Landing occurred at 9:54 a.m., April 20, 1994. Mission duration was 11 days, 5 hours, 49 minutes. NASA image. NASA STS059(S)07

From the MS-1 seat, I shot video of our reentry aboard Endeavour. Jay took this shot after landing from the middeck ladder on the port side. STS059-47-11

Post-landing, I felt laden with extra weight, as if my launch and entry suit were made of lead. That video camera feels like fifty pounds. Getting out of the seat took every bit of strength I could muster; I had to force my muscles to slide over and lower my “two-ton” body down the ladder.

Jay Apt on the middeck took this shot of the ground crew at Edwards opening Endeavour’s hatch after our April 20 landing. NASA STS059-47-22

The ground crew is the first to sample the interior atmosphere of our sealed spacecraft, after six people have lived in that volume for 11 days. Our noses were used to any aromas, but they no doubt smelled the combined odors of our wet trash bin, the shuttle waste control system compartment, our dirty laundry, and six bodies who hadn’t showered in more than 10 days. They may have wanted to just close that hatch up again!

Tom,

Great! My best memories are of the crew and the Southern Aurora. It was a great group of folks to work with both on the ground and in Space. I remember the comment Linda made during an interview that generated that strange response from the ground. I would like to forget about the air in the water and everything that went with that. Chili falling asleep on the middeck while sending Emails late at night. Jay maneuvering the vehicle under Chili’s watchful eye. Rich and I waiting for anyone to get sick so we could actually give a real shot. I remember your enthusiasm at seeing all of it the first time and your incessant comments into the tape recorder so you could piece all this together later. And I remember the incredible feeling as we blacked out the lights and floated through the Sothern Aurora – like passing thorough something that was alive. But most of all I remember being able to eat a juicy hamburger with tomato and lettuce after we landed and then heading home to wives, husband and all the kids. Great memories!

Sid